Anyone who says genetically modified foods are harmless is

not paying attention to biology.

Just like their fingerprints, no two people have the exact

set of genetic materials. Most of the variations and innocuous, like eye or

skin color, hair texture, all these small differences that give each of us our

unique looks and personality.

Some of these genetic differences create no apparent

difference whatsoever between two people. But these differences CAN show up later when the

environmental conditions change. One specific set of apparently irrelevant

genes in a person may allow that person’s white blood cells to react more

quickly when an unknown chemical somehow enters our food supply. Whereas those

individuals who lack that gene get sick, those few individuals who possess that

odd, rare gene live better.

We

humans don’t change very rapidly. Malaria became a serious disease for the

human race long ago. It took a while, but over thousands of years, some evolved

immunity to it.

It

took as much as 20 generations, hundreds of years, for humans to evolve light

skin and blond hair. Those changes were driven by an ongoing need to absorb

more UV radiation from the sun to make sufficient Vitamin D as we moved into

higher latitude with reduced sunlight.

Eventually, only people with that useful genetic trait may

exist in the world, or a large region of it, the others having been very slowly

eliminated from or reduced in the gene pool. This is not meant to be cruel or

racist; it’s why our world is populated with the tremendous variety of people

we have today. Those of our ancestors whose bodies could better cope with, say,

the Yersinia pestis bacteria or the H1N1 flu virus survived the Bubonic Plague in the

mid-14th century and the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918.

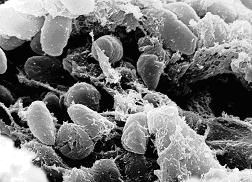

Yersinia pestis bacteria H1N1 flu

virus

People

who had within their genetic makeup an extra resistance to either that

bacterium or that virus survived. Those that didn’t, died, and ended their

genetic line. Such genetic mutations occur slowly and randomly in humans, and

are then passed to the offspring of those who possess it. We can’t do much to

either speed it up or stop it from happening.

Bacteria

generate random mutations in theior genetic makeup much more rapidly then we

humans do. And bacteria, and for that matter viruses, have an extra “genetic”

trick we humans lack: they can swap genes. And I don’t mean to mix their genes

in their offspring, as we do every time we make a baby. A living bacterium can

amble up to a complete stranger bacterium and exchange genes. Each one tends to

offer up what seems to be most effective in the environment they currently live

in.

So

if, by mutation or ay other means, a single bacterium develops resistance to,

say, an overused antibiotic drug, chemical, or a genetic change on a species

they prey on, they can quickly pass that on to all their neighbors, who pass it

on to their neighbors, and so on. In a relatively short period of time, virtually

all the bacteria which haven’t already died from exposure to the antibiotic or

chemical are immune to it. We have created superbugs.

All

living things evolve over time in the sense that their exact genetic makeup

changes. It seems that the more complex the creature, the slower this process

is.

So

what is the point of all of this? Simple. If we rapidly change our environment,

because of widespread and heavy use of drugs, chemicals or even genetically

altering our food sources, we will trigger a massive “biological war” with the

bacteria, insects and weeds that already attack us or our crops, just as

occurred naturally when bacteria exchanged genes and became resistant to

penicillin. We are forcing pests to become superbugs, super weeds, etc. Genetically

modifying our crops will, in the long run, make life miserable for us humans,

just as antibiotics eventually created bacteria and viruses we can’t defeat.

Are

you listening, Monsanto?

No comments:

Post a Comment